Wartime CEO: Running a War Room (1 of 2)

Written by Dave Bailey

If your company faces an existential threat, read this.

All bets are off.

That lead investor just pulled out.

Your cost of acquisition just doubled.

Your biggest customers are leaving.

You stare at the spreadsheet. Nothing adds up. Without swift action your runway will shrink until a crash is imminent.

What do you do when your worst-case scenario becomes a reality?

Welcome to wartime

In The Hard Thing About Hard Things, Ben Horowitz paints a vivid picture of a wartime CEO up against an ‘imminent existential threat’.

In the 12 years building tech companies, I did more than my fair share of layoffs. I've shut down companies, fired co-founders and had investors pull out at the last minute.

But as a CEO coach for many years, I've seen even worse.

Mike Tyson said, “Everyone has a plan until they get punched in the face.” And that’s why I’m writing this series: to give you a blueprint on how to react when life deals you a painful blow.

The series comes in two parts:

- Part 1: Running a War Room (attack)

- Part 2: Making Cuts (retreat)

Attack: running a war room

War rooms are used by military leaders to discuss tactics and strategies in a state of war. In your case, you’ll create a dedicated space for your team to work intensely on your plan of attack. If you have an office, you might take over a meeting room, otherwise it might be a dedicated video-conference link.

When you think of military operations, you may think of a controlling leader with thousands of soldiers following their orders without question, but the modern military couldn't be further from that. When I interviewed British Army Officer-turned-CEO, Paul Ford, back in 2020, he clarified it for me:

“People think that [in the army] there’s someone who tells someone who tells someone… but it isn’t like that. Wars are chaos, so the concept of empowerment is entirely built into the model. It’s called Mission Command: you tell people what you want to achieve, not how to do it. [In a war], they could be cut off from communications and have to use their initiative.”

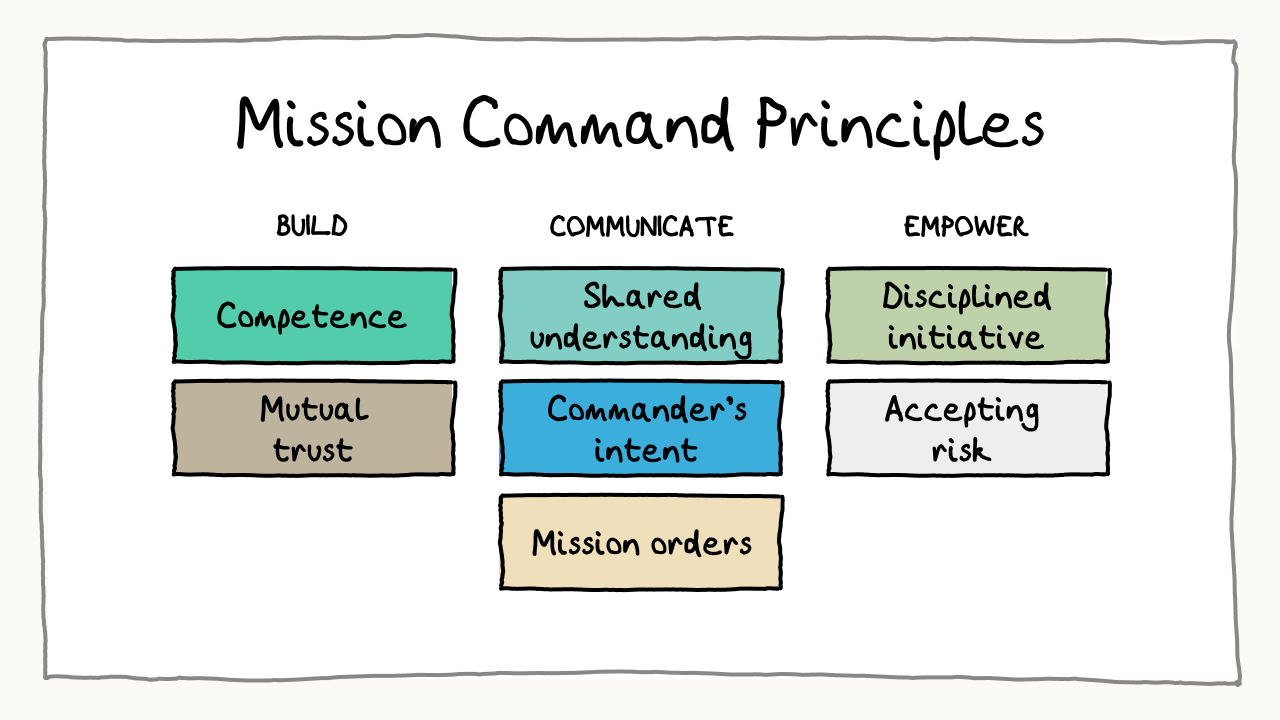

Mission Command, advocated by the militaries such as the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom, is based on seven core principles:

- Competence

- Mutual trust

- Shared understanding

- Commander’s intent

- Mission orders

- Disciplined initiative

- Accepting risk

These principles are extremely helpful when running your war room. I’ll run through each of the seven principles, and explain how they can apply to your war room.

As you read on, think of yourself as commander, rather than CEO. After all, we’re at war.

1) Competence: assemble your best leaders

Mission Command relies on the competence of you and your leaders. It’s critical that the teammates you assemble in the room are your best and brightest.

You must also show competence as a commander. Retired US Army Colonel, Eric Lopez, shares 10 tips he received from his commander that stood him in good stead. As I couldn’t have said it better myself, I’ve included the video.

2) Mutual trust: lead by example

It’s clear that you’re more likely to delegate to those you trust. But it also goes the other way: if your team believes you trust them, they will be more willing to use their initiative and follow your lead. So how can you build trust during wartime?

Col. Sharpe Jr. and Lt. Col. Creviston compiled some useful trust-building research here:

- Reduce physical distance e.g. try to co-locate

- Create positive personal interactions e.g. arrange a dinner

- Acknowledge past accomplishments and reputation e.g. celebrate small wins regularly

- Highlight common values e.g. write your values on the walls

However, the biggest driver of trust and morale (known in the military as esprit de corps) is the actions leaders display. Sharpe and Creviston write:

“Leaders of confidence, competence and high moral values exude esprit de corps and provide a contagious commitment to the organisation and its norms.”

3) Shared understanding: meet regularly

Creating a shared understanding of the situation, objectives, and each other’s roles is fundamental to Mission Command.

War room meetings may take place anywhere from from a couple of times a week to a couple of times a day, depending on how quickly the situation is changing. You’ll review metrics, share progress and learnings from the trenches, and coordinate as plans evolve.

You may use real-time dashboards, TV screens, posters and whiteboards to make important information visible, such as KPIs, recent developments and the commander’s intent.

4) Commander’s intent: outline the unifying goal

The Commander’s Intent is a description of the purpose of the operation. It must include the wider context, the key objectives, and the desired end state.

It’s worth crafting it concisely and precisely since it will become a focal point for the operation and will be used to make decisions when you’re not present. If it’s more than a paragraph, it’s too long. You may even create a five-word mantra that sums it up.

When the business is under threat, emotions can run high. Delivering the Commander’s Intent is your call to arms. Use a combination of vision and vulnerability to win hearts and minds:

- Vulnerability: I don’t have all the answers, we’ll need to trust each other and give our all, and there’s only limited certainty I can offer.

- Vision: If we give it everything we’ve got, not only are we in with a chance, but we won’t have any regrets. So here’s our intent…

5) Mission orders: describe the results you want

A mission order might sound prescriptive, but it actually focuses on the outcome, not the method.

“Mission orders are directives that emphasise to subordinates the results to be attained, not how they are to achieve them” — Mission Command, ADP 6.0, Department of the Army

Unlike micromanagement, mission orders rely on your team’s disciplined initiative. After giving orders, you need to check in with your team and provide additional direction and support as required.

6) Disciplined initiative: exercise freedom and responsibility

The expectation set in the military that the team will use their initiative to deliver results that are (i) aligned to Commander’s Intent, and (ii) coordinated with the efforts of other team members.

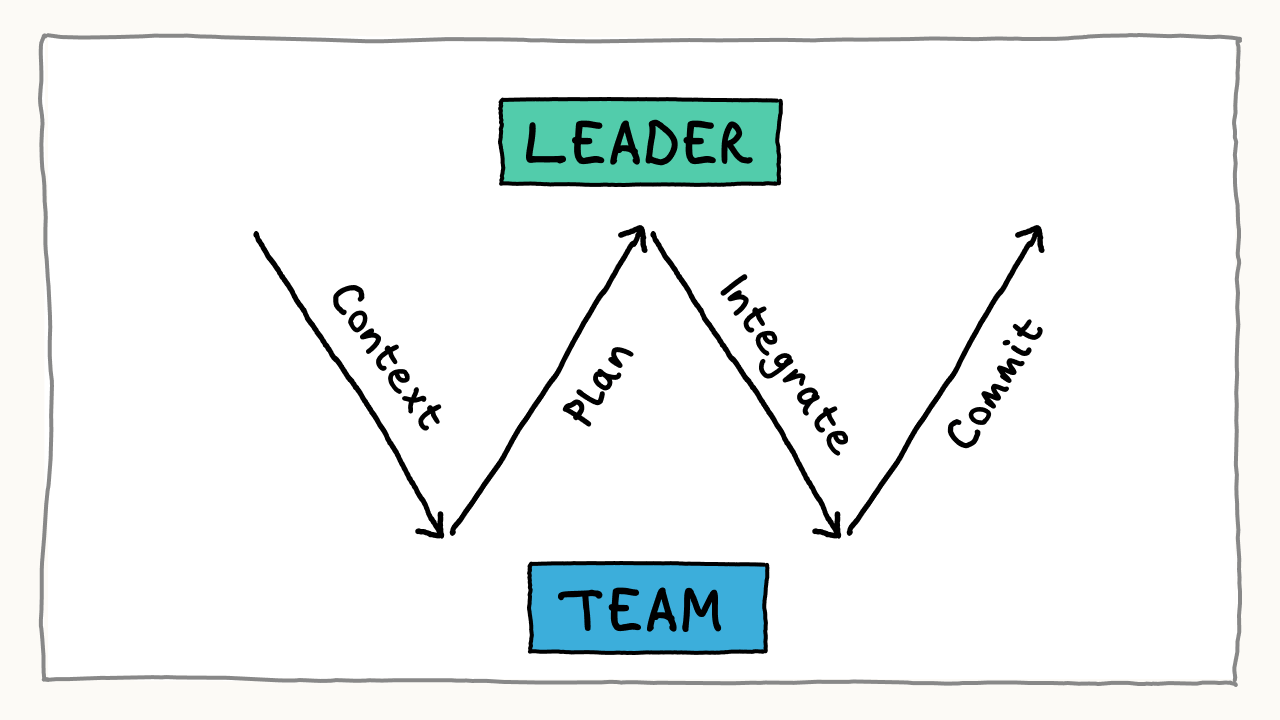

The ‘W’ process provides clarity over the roles of leadership and teams in the planning process.

The ‘W’ process provides clarity over the roles of leadership and teams in the planning process.

- Step 1: Leadership sets the context (Commander’s Intent and Mission Orders)

- Step 2: The team creates their plans (Disciplined Initiative)

- Step 3: Leadership integrates their plans

- Step 4: The team verbally commit

Under this process, the Commander is responsible for ensuring plans fit together. If the commander isn’t available, the team must proactively share their updates—progress, priorities and problems—between themselves.

7) Risk acceptance: measure before you cut

Given the same amount of intelligence, timidity will do a thousand times more damage in war than audacity — Carl von Clausewitz

Taking risks often brings with it great opportunities.However, risks must be analysed by you and your team to ensure the benefits outweigh the costs.

In my first startup, we wanted to boost sales to rescue a failing fundraising effort. My partner and I came up with an idea for a marketing stunt that could reach thousands of potential customers.

The stunt came with a big price tag—equivalent to the monthly cost of the business. The chances were slim, but we reasoned that if it worked, we’d have a better chance of convincing sceptical investors. So we ran with it.

It was a bet-the-house moment and it felt thrilling… until the campaign turned out to be a flop.

Looking back, we didn’t properly estimate the risks, and we took an uninformed bet. If our existing investors hadn’t come out to rescue us, the company would have gone under. I learned a valuable lesson:

Never gamble with your company.

Analysing risk and making intentional choices is playing the odds. For example, jumping on a plane to meet a high-potential investor is a risk, but it doesn’t put the entire company in jeopardy.

Redefining success

The Commander’s Intent will spell out the desired end state. It’s tempting to define success as meeting that end state. However, I’d like to suggest a different definition: success is survival.

Every mission order completed is worth celebrating. Every hard-earned learning is worth celebrating. Every week that you survive is a success worth celebrating. Don’t forget to celebrate the small wins.

Next up: knowing when to retreat

Running a War Room can help create the conditions for inspiring team spirit and collaboration. Small, empowered teams can generate incredible results.

However, as CEO, it’s also your job to manage your resources. to ensure you can weather the storm. Decisions involving layoffs are among the hardest any leader has to take, so in the next part we’ll go through how best to approach this together. Until then, godspeed and good luck.

Originally published 4 Aug 2023

How do top founders actually scale?

I’ve coached CEOs for 10,000+ hours—here’s what works.

Join 17,000+ founders learning how to scale with clarity.

Unsubscribe any time.